Gastro-Spirituality with Jenny Lau

Photo by Ming Tang-Evans

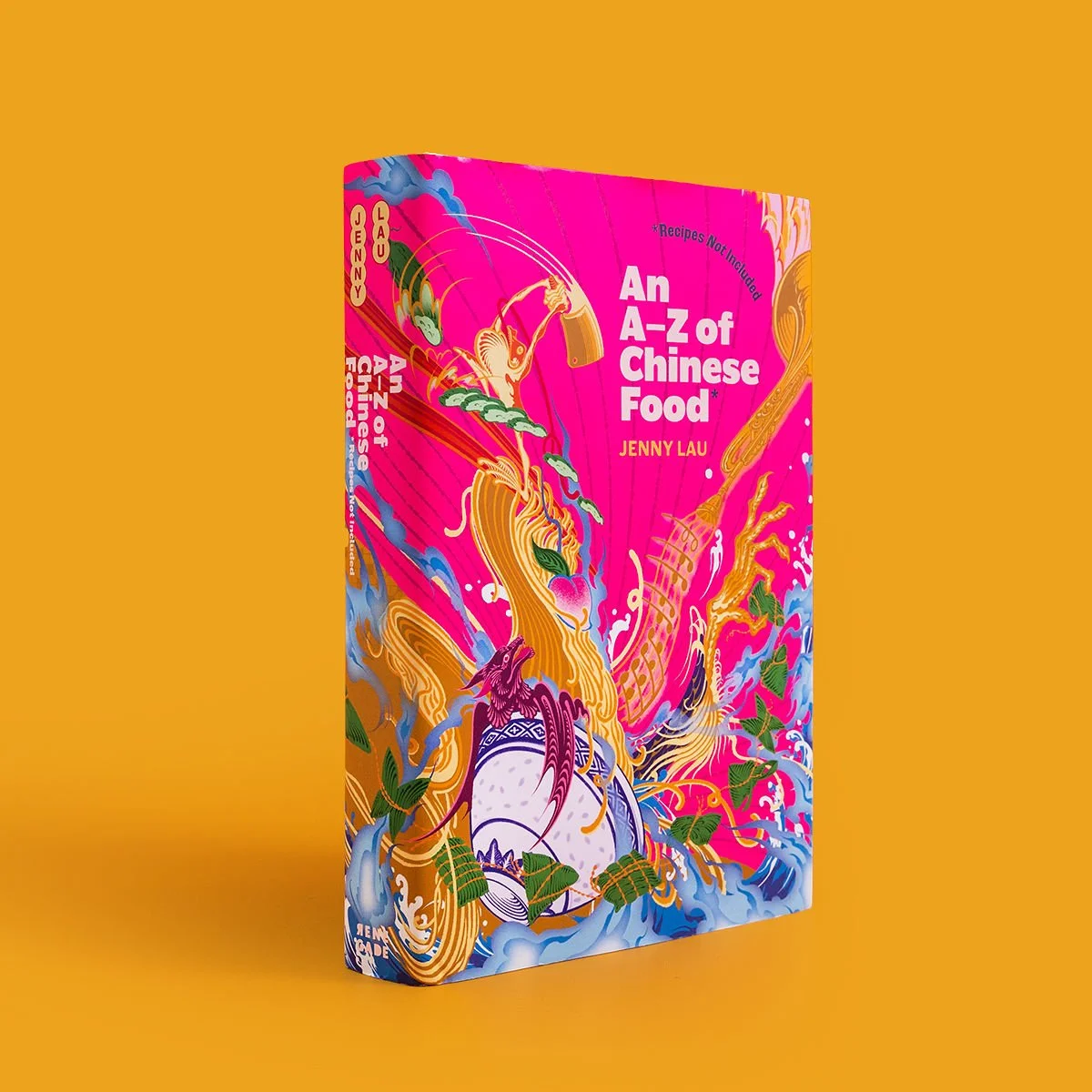

This month’s book club pick: an A-Z of Chinese Food, by Jenny Lau.

An A-Z of Chinese Food began life as an essay series on the multidisciplinary platform Celestial Peach, founded by Jenny Lau to tell and connect stories about the Chinese diaspora.

As well as writing about food and culture, Jenny does extensive grassroots work as a cook and community organiser, and if you follow her on instagram you’ll be well versed with both the incredible food events she puts on and with her extraordinary skills in the kitchen. As I say to Jenny in this episode, what makes her such a remarkable voice in food writing is her focus not just on documenting but also on doing; she’s at the heart of the communities and community activity that she writes about and this gives her work a unique perspective. She’s hugely involved with the ESEA Community Centre - formerly known as Hackney Chinese Community Services, organizing events and working in the kitchen and talks to me here really movingly to me about the importance of intergenerational relationships when building connections.

Much of the work she’s done, in Jenny’s own words, has been in the search to define her own cultural identity, navigating feeling pulled between east and west. She’s worked tirelessly to reclaim and redefine Chinese food and culture from tired tropes and cliches and the A-Z of Chinese Food is an ‘anti-glossary’ - not concerned with overdone conversations around authenticity but instead a new way of thinking about Chinese food.

An A-Z of Chinese Food is out now. Find all of the Lecker Book Club reads on my Bookshop.org list. [aff link]

Support Lecker by becoming a paid subscriber on Patreon, Apple Podcasts and now on Substack.

Music is by Blue Dot Sessions.

Transcript below the embed

[00:00:00] Jenny: I think one of the benefits of the way I've approached food is to sort of be this outsider in both sense. You know, I'm an outsider in a white western world, but I'm also an outsider in the Chinese food world.

So a lot of my peers in the Chinese food industry were, for example, takeaway kids or trained as chefs, and so they're kind of embedded in that, that system and. They have this emotional connection to food because food for them was livelihood, it was family, it was business, it was sustenance. So I almost was able to take this anthropological and ethnographic approach to food coming at it from an outside point of view.

[00:00:43] Lucy: Well I would love to start, by talking to you about the idea of writing an A-Z, and I'm getting straight in here, not even gonna ask you to introduce yourself. Your book is called The A-Z of Chinese Food.

Why did you choose an A-Z as the format?

[00:01:01] Jenny: I thought an A to Z would be quite a fun challenge. I think I really relish anything that has a structure to it. I guess it could have been any kind of listicle, but I thought A to Z was fun because you can pretty much

Marker

[00:01:15] Jenny: pick any topic for each of those letters.

But crucially, I also like the idea of being subversive with the A-Z because quite often people look at food related A-Zs and think that, oh, well it's going to be a compendium, or it's going to be a glossary that explains different ingredients or different dishes or different techniques. And I really wanted to subvert that expectation.

So you're not going to get, well, you do get T is for tofu, but you don't get T is for how to cook tofu.

[00:01:45] Lucy: Mm-hmm.

Mm. And the, yeah, there's definitely, that was something that I felt I was thinking about while I was reading the book, that there is this implication of like, definitiveness with an A-Z and you are very explicit from the start that it's not, it's not that.

And even within, there's subversion, even within the kind of use of the letters such as the last chapter which is Zed is for

[00:02:09] Jenny: Zongzi

[00:02:09] Lucy: Thank you. But you talk about how the zongzi is also known by different words that do not begin with Z. So I really liked that kind of like even within the structure that you had chosen, it was kind of like, it's not what you expect.

And I think that really spoke to the kind of playing around with language in the book and I guess like a cultural critique of language within Chinese food as well, which I really loved. You talk about not including recipes as a kind of act of resistance, talk to me a bit about that.

[00:02:43] Jenny: I think that anyone who operates in a food space, which I have done for a while there's always an expectation that you have to commodify yourself in some way. And I guess the two ways in which

Marker

[00:02:56] Jenny: we commodify ourselves are firstly either by selling food, you know, in the form of a restaurant or as a chef.

And the second way would be to sell recipes. And I was constantly being asked like, when are you going to write a cookbook? When can I get that recipe? I think there's this incredible pressure on you to create something definitive to go back to that word you chose, present it in the most palatable way possible to an outside audience.

But I find that in doing so, there's this compromise that takes place and you're both compromising towards your. Consumer because you are, you're kind of changing something very essential and trying to define it. Something to define something indefinable into something on paper. So what comes across is.

Something that is almost to use the word inauthentic. And at the same time, you're also compromising towards yourself and towards perhaps your culture or your heritage. So it goes hand in hand with this notion of authenticity. I think the fact that you are expected to somehow document a living, adapting, breathing cuisine, and to be authentic in doing so.

[00:04:15] Lucy: Mm.

That it is interesting that cookbooks are kind of the dominant form of mainstream food culture, right? Like I think about that a lot, especially as somebody that is super interested in food and will never write a cookbook. There is an expectation around it, sort of in any field, but they are so commodified that we produce so many of them.

It's got to the point now where you wonder what there is left to write in a recipe because it is, I mean obviously there are vast swathes of still uncovered,

places and foods within that, but they've almost become meaningless as a form because there are so many of them. So yeah, I think that idea of resisting commodification is super interesting and that is so present on social media as well.

Like you will see so often people are just like recipe. They feel this entitlement to learn something from you or to like, take something from you. Have you experienced that?

[00:05:08] Jenny: Exactly that and you know, that recipe? Comment is one of my greatest bug bears. It goes to this notion of transactional exchange.

The way in which, especially as immigrants or diaspora, we have this pressure to create something that is of useful transactional exchange. And food for the Chinese population has always been been that way to assimilation and integration,

Mm-hmm.

Which means we have to make our food tasty, commercial palatable cheap. But I very much resist commodified transactional exchange, which is why I'm... my greatest passion is community work and operating in community spaces, doing grassroots activities and projects where there is very little to no transactional exchange. Instead, what's happening is a kind of cultural exchange.

[00:06:05] Lucy: Mm.

Mm.

[00:06:06] Jenny: So for example, I will host food meetups where we all bring a dish that to share, but no money changes hands. And so when no money changes hands, what are you forced to do?

Well, you're forced to exchange other things, which is conversation and stories and mutual understanding.

[00:06:25] Lucy: Yeah. And there's a kind of the power dynamic is different.

There can be a power imbalance within sort of, it can go both ways. Like the person who is holding the recipe has the power, but also then there is another power dynamic, especially within kind of like a racist western system where there is an expectation from like white people, for people of color to give them access to their cultural knowledge.

So yeah, that idea of a cultural exchange feels really powerful in that context as well. And that makes sense within the work that you do. For sure.

And I guess that also speaks a little bit to what I wanted to ask you next, which is right at the beginning of the book you say, "I belong to the world of translators", and I love this idea of translation. You talk about translating accurately versus translating truthfully. What is the difference between those things for you in the context of food?

[00:07:22] Jenny: Mm. So. That's a really interesting one. We are so obsessed with translating accurately and people will argue over, well, you know, what words or what sentence formation is the most kind of accurate way to, you know, put across this ancient Chinese poem, for example.

But if I think about how to perhaps translate that poem truthfully, or, or, or even authentically, it would be about how to get the essence of that poem across. And maybe the essence of the poem is actually a feeling that can't be described or it's, you know a sentiment. And I think, again, this goes to the idea of commodifying something.

Because when we commodify something that has these kind of like cultural boundaries and or has to go through several steps in order to sort of be translated as a word that this essence is lost. And that's kind of why I, I landed on this conclusion that, well, I don't need to translate myself anymore.

Mm. And often when you speak to people who are bicultural multicultural, they will often talk about this lifelong niggling, you know, in their very core, which is that I constantly have to translate myself if I'm an person of color in a white world, I'm constantly have to translate myself for white people.

Then back home, I have to translate myself back to my parents who perhaps, you know, perhaps we don't speak the same language fluently or perhaps when I go back home. Like for me, when I go to Hong Kong, I feel like everyone knows that I'm an outsider. So it's just very it's very cathartic to allow yourself not to have to translate yourself.

Right. And I guess it all came out in this book in which I just, I just write authentically for me.

[00:09:16] Lucy: Mm-hmm. That really comes across for sure. Yeah. You say in, in this same chapter where you talk about translation you describe how so much of the information that Britain as a whole, has access to about Chinese food, and I guess Chinese culture more broadly, has been through the translation of white Western scholars, which must have had a huge impact on how that culture has sort of been like rebuilt, almost like reconstructed here. Is that something you've sort of noticed yourself, like kind of knocking up against as you've learned more yourself?

[00:09:50] Jenny: I think so. Even if you look at, you know, let's go back to cookbooks for example. There have actually been Chinese writers who have published cookbooks in English, technically flawless, you know, absolutely perfect instruction since the 1900s. Hmm. But they're kind of overlooked. And and this is in the States and in the uk I'd say they're kind of overlooked. And often I hear people, you know, referencing the similar, you know, Chinese cookbooks of a similar technical standard and written by white authors who are academic and you know, equally well researched and it goes so much to this perception of who is an authority and who do you trust.

I think, you know, perhaps it's not the case now, but certainly at least 20, 30 years ago, you would maybe look at a Chinese, two versions of a Chinese cookbook one written by someone whose name you can't pronounce, even though that person's Chinese and maybe the, the other is a white author.

And you'd go, you know what? I kind of trust that one because that person's going to explain it to me in the language I understand and make sure it's not too scary and, you know there's nothing too icky about it.

So

So. I think it's changing now, but at the same time I've moved beyond that. You know, I don't want to write a cookbook that is technically flawless.

I actually want to go beyond the food. And a lot of my peers in the Chinese community are the same. You know, we're writing about much more complex topics now.

[00:11:30] Lucy: Yeah. Yeah, yeah. Yeah. Well, I guess that, that it makes sense because you, you talk in the book about how food is basically how you stitch together your multilingual story. Can you tell me a little bit about that process? 'cause it happened... it wasn't a childhood thing for you, right? It was something that you started to figure out more as an adult. So tell me a bit about how food fitted into that for you.

[00:11:58] Jenny: Sure. I came to food. Much later in life, I'd say in my early thirties.

And I'll caveat by saying, I grew up in Hong Kong from the age of 0 to 11. So I grew up eating really beautiful kind of Cantonese home cooking. I grew up going to wet markets, which was the way you would shop for ingredients. It is now becoming a much rarer sort of form of, um. Provisioning in, in Hong Kong, so people are going to supermarkets now.

But I remember going to wet markets with my mom and shopping for fresh ingredients there. And I guess you'd, you could say that I grew up eating Chinese food or as I called it, food. And when I moved to London at the age of 11, I remember my diet changing, just, just overnight. It was like completely drastic.

Because I also went to. Secondary school. So I started eating school dinners. My mom would cook, you know, whatever she could buy at the supermarket. So we ended up eating quite, I, I think British, very British ish meals. Chinglish, I call them. Sort of nondescript. I don't think I can really remember what we ate at home.

Mm-hmm. And it was much later in life, maybe in my early thirties, when I knew that there was something in my life that was very lacking and I felt like I was so out of touch with where I came from. And with my Chinese culture and with my Chinese background. But I do remember that every time I went to Hong Kong to visit my dad, whatever I ate there, even if it was, you know, junk food that I bought on the street. I just felt really good.

And at first I thought maybe it was like a, a kind of physiological thing. Maybe it was a nutritional thing, you know, that I should eat more Chinese food, literally. But I think there was something almost like gastro spiritual going on, if that can be a word. Yeah. Let's call, let's say that's a word now. Something gastro spiritual was going on,

Lau, 2025.

Yeah. Word of the year. OED. And I think it was to do with what I was eating, but where I was eating it. Mm. So I kind of embarked on this journey to sort of educate myself about Chinese cuisines.

And that kind of went hand in hand with this exploration of community, specifically the diaspora community. And in fact, my interest in diaspora identity quickly overpowered the interest in food itself. But I found that food was the best way to get people to talk about identity because... the Chinese diaspora is so diverse.

We don't all speak the same language. We don't all have the same experience and migration journeys that, you know, I had this interview series where I interviewed a hundred Chinese diaspora from around the world, and, and I would open or close each interview with what does home taste like? And in a way that gave me more I needed to know about their identity than.

If I asked, what is your relationship to, you know, your identity, which is kind of a awkward question in itself.

[00:15:11] Lucy: Yeah. How do you even answer that question? Yeah, yeah, yeah.

[00:15:13] Jenny: Because in asking what does home taste like? They then had to define what is home.

[00:15:17] Lucy: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. What's the answer to that question for you?

[00:15:22] Jenny: It is in the chapter H is for home cooking, of

[00:15:25] Lucy: of course.

[00:15:26] Jenny: Yeah. And I kind of land on something that is somewhat multi-sensory. Mm. And very nostalgic actually.

[00:15:33] Lucy: Mm-hmm. I really enjoyed the, the, the sort of explicitly multisensory

sensory section where you describe the sounds, you know, the sounds of like cleavers hitting bone and, and the smells and the textures.

And yeah, I think that's another thing that food brings to a lens on our identity. That it's not just language or words, it's kind of like this whole experience. Yeah.

Connected to this. There is a very strong trope in, I guess like food. I dunno if it's like a specifically, it's very, very prevalent in Britain.

The kind of trope of the parent or grandparent being the kind of like central core or like the beating heart of an individual's food culture. This is very clear from the dedication onwards in your book that it's not the case. You'll have to correct me on the exact wording, but it's something about to my parents who never taught me to cook or to speak Cantonese great.

Like what? Is your, how do you feel about this trope and what does it mean to you and why do you think it's so persistent? If I can ask you three questions in one go!

[00:16:42] Jenny: I think it's kind of irksome and that's why I wanted to explode that myth throughout the book.

And there are several chapters where I look at the relationship of diaspora Chinese or diaspora in general to food via their parents or via their kind of ancestral lineages. Mm-hmm. I think firstly it's this kind of origin story or authenticity story that people love to buy into. Because if you say that my mother, my grandmother taught me how to cook, or that this is my grandmother's recipe. There's no contestation. You know, no one can call you up on it, and thus, that's true.

Thus, your recipe is authentic. And in a, in a way it is authentic, right? But then it creates this stupid benchmark for authenticity, which is that, you know,

[00:17:32] Lucy: it has to be blood. It's

[00:17:33] Jenny: It has Is is it, you know, did you inherit your talent, you know, via DNA? Yeah. Then what it also does, is it, the problem is it kind of... it enforces these ideas of preservation and of traditionalism onto food, especially diaspora cooking. Mm-hmm.

[00:17:54] Lucy: Mm. Yeah. It is particularly prevalent in diaspora cooking, right?

[00:17:57] Jenny: That's right. Especially in matriarchal kitchens where, well, yes. You know, I think I have this line about dumplings, you know, the rolling of dumplings, almost being this metaphor for knowledge and sort of bonding, you know, being handed down through the generations. And I do want to contest that because there are other ways that you can bond with your parents or maybe you don't at all, you know?

And I guess the other problem about that is that there's this overriding sort of trope that food is a love language and food is how we express love. It's something I hear all the time in Chinese culture. You know, food is love language. Chinese parents don't say I love you. They hand you a plate of cut fruit.

It's very simplistic, and it's very dangerous actually, because at the same time as food being a love language, it can also be this form of toxic control. It can be. I know that quite often you have Chinese parents who are very overbearing and they will use food to kind of keep the apron strings short, as it were to constantly have their children sort of in their hand.

Another trope is that, you know our elders will simultaneously force feed and then fat shame us. So people do have these very complex relations to food that we perhaps sometimes don't want to call up and question.

[00:19:17] Lucy: Yeah. It's easy. It is definitely sort of easier and neater to not delve into that relationship too deeply. You also talk about in the book how you don't feel like you have an emotional connection to food, which I feel like sort of leads on from that.

And I, so I think, I can't remember, was this the, was that, is that in the home cooking chapter where you talk about doing a video audition for a cooking segment on a TV show, and you feel like you've implicitly failed a test when the auditioner, whoever the producer was asked you... how you feel when you eat Chinese dishes and the, the answer is that it's, it's not really like that, right, for you?

[00:19:58] Jenny: No. And I think this goes back to me coming to food as an outsider and even Chinese food. Mm-hmm. Because. I didn't, you know, I have no association of Chinese food, particularly with my parents or with love.

That's not to say I don't love my parents. Right.

[00:20:15] Lucy: But it seems wild. You have to qualify that.

[00:20:17] Jenny: It seems wild. And I think there are several things here. I think one is that there's always this expectation that women in particular have a very emotional connection to food because, you know, women are primarily caregivers and...

[00:20:32] Lucy: yeah,

[00:20:32] Jenny: There's this notion that mothers, aunties, grandmothers are the ones who kind of imbue, you know, embed love into their cooking. Whereas if you look at the kinds of questions that are asked of, let's say, male chefs, particularly very scientific ones, you know, Heston Blumenthal and all of that. I know Heston Blumenthal uses nostalgia as a kind of recurring thread in his cooking,

[00:20:56] Lucy: but he's allowed to do that without a family connection, right?

[00:20:58] Jenny: He is, and he's allowed to do it in a very scientific way. Yeah.

[00:21:01] Lucy: Mm-hmm. Yes. Yes. Yeah. I love that comparison actually. That's so true. Like, no, has anyone really ever asked Heston Blumental about his grandma? Like, I mean, I guess they have, but probably not in the same way. Yeah, yeah.

[00:21:14] Jenny: I think one of the benefits of the way I've approached food is to sort of be this outsider in both sense. You know, I'm an outsider in a white western world, but I'm also an outsider in the Chinese food world.

So a lot of my peers in the Chinese food industry were, for example, takeaway kids or trained as chefs, and so they're kind of embedded in that, that system and. They have this emotional connection to food because food for them was livelihood, it was family, it was business, it was sustenance. So I almost was able to take this anthropological and ethnographic approach to food coming at it from an outside point of view.

I started I started with those hundred interviews before I could, I even turned the questions on myself. Mm-hmm. And. In a way, it gave me this distance to it where I could look at it a bit more objectively before deciding what my emotions had the potential to be. Mm-hmm.

[00:22:15] Lucy: And also because, so you know, obviously your work, your work has involved a lot of writing, but your work has also involved probably arguably more doing, and I dunno if that's true of a lot of food writers.

I think there is a lot of kind of like absorption, but not necessarily the sort of work you've been doing. And I find it, you know, it's sort of interesting to hear you describe yourself as an outsider and I completely respect that like, you know, that kind of like central bit of how you feel but to see your work at the ESEA Community Centre is to see you as this, you know, the kind of like, you're like kind of at the heart of this amazing hub.

So maybe tell me a little bit about... 'cause it's, this is something that you built, it's not something that kind of you stepped into naturally. Tell me a bit about building that community and what it means.

[00:23:03] Jenny: I think you've kind of nailed it there. I constantly want to learn by doing and absorb by doing, I. That center is like a second home to me, and it is there that I was able to build, actively build this grassroots, my grassroots community, not the grassroots

[00:23:24] Lucy: Mm.

[00:23:25] Jenny: but a grassroots community around me, one by one.

And this includes, you know, people who I physically see and meet up with and have conversations with. As well as the extended network around the world. You know, whether it's through online interactions, through interviews, through collaborating on projects where we never actually physically meet, but we, you know, do them online together.

So I think I see this as a form of almost contextualization of my identity, and it's, it's been this incredible process where I started not really knowing who I was or what my place was in the world. And the more I built this. Satellite of people around me or a universe of people around me. Mm-hmm. Not to say that I'm the sun, but everyone is.

No, everyone is the sun. And everyone should be constantly padding out and contextualizing their own identities through these stories that are kind of mirrored and refracted back to them. Mm-hmm.

Again, it, it was just so cathartic because it's something clicked where I was like, oh, I'm just one cog in this massive sort of moving, amorphous sort of entity that is the Chinese diaspora, which, you know, also simultaneously is and isn't a diasporan community because mm the only thing that connects us is that, you know, we all came from China at one point. right?

That's the that's the thread. But yeah, so I think what I've laterally realized, actually very recently, is that the reason community that that space has been so important to me is that I'm constantly searching for this feeling of home and of family. And that's not to say that I don't love my nuclear blood family, but I also felt like I was lacking something because in moving away from Hong Kong, I moved away from my father's extended family.

[00:25:18] Lucy: Mm-hmm.

[00:25:19] Jenny: My mother had already moved away from her massive extended family in Malaysia and she'd moved when she was 18 to the UK and never returned.

And so I was already twice removed from my mother's side and once removed from my father's side, and that's been for a good 30 years. So I think being able to choose your family is such a privilege. Yeah. And I'll do anything to keep it around me.

[00:25:44] Lucy: I think there's also that, there's also some sort of and I don't quite know how to articulate this, but it's something I think about. I think there's so much prioritizing of kind of blood family, whether that's parents or siblings or like children that I think it's really powerful to, you know, like build really strong connections with people who aren't related to you. Like, and that's so important because that is how we build like a world that feels better or more equitable or like however you wanna view it. That feels so important.

[00:26:14] Jenny: Yeah. I think nowadays there's this overuse of the word community, actually.

[00:26:19] Lucy: actually. Yeah. Yeah. That's fair.

[00:26:20] Jenny: Yeah. But I think it really is a community at the, at the ECCC, what I love is, and I, I, I've taken this for granted now, but I'm there at least two, twice a week, sometimes three or four, and it's totally intergenerational.

You know, I'm hanging out with people from the age of, I'd say 20, all the way through to 80 on those days. In the kitchen where I now work we are often three generations in the kitchen. Wow. You know, so the head chef is 20 years older than me, so she's like an older cousin, a fun older cousin. Then we'll have volunteers who are half my age.

We'll be speaking at least four different languages in the kitchen. And what I realized about being surrounded by elders in particular is that I was able to remake and in a way, heal my relationship to my mother. Oh. Through interacting with them. Because you are kind of, you are almost given this you are given permission to sort of try out things on the elders that you, that would be too emotionally, sort of, that would be too emotional or too maybe too close to the heart if you were bringing up with your, with, with your own mother.

[00:27:36] Lucy: Okay.

Okay. Yeah.

[00:27:37] Jenny: Yeah. I dunno how to describe it, but they really saw, they really helped me to see my relationship to mom in a different light.

[00:27:44] Lucy: That's amazing. And, and does that, has that meant that you've had conversations with your mom that you maybe wouldn't have? Or has it felt just a bit more like within inside yourself?

[00:27:53] Jenny: Totally, and I, I think.

I humanize her more because, you know, we, we, I think all of us are guilty of this. We sort of dehumanize our parents and so, oh

[00:28:04] Lucy: absolutely. It's, it can bere like I think especially if, if you've been close to your parents in the sense they've been very present, it can be very difficult, very difficult to see them as people.

[00:28:14] Jenny: Absolutely. So, you know, at the center, a lot of the elders that then... they're not really similar to my mom because, a lot of them came to this country maybe almost 50 years ago, you know, as immigrants and something happens to immigrants who don't perhaps fully integrate.

They kind of developed this interesting persona, I feel. I'm not a psychologist, but I have observed a lot of the elders. Yeah. I've observed a lot of the elders who come to our center and there's a reason they come to the center, which is that they haven't fully integrated, they haven't, you know, fully mastered English or met a lot of them don't speak English at all, so they need the help and the services that the center provides.

They need translation. They need, you know, handhold, they need that socialization

Mm. Because they're isolated otherwise, and I've discussed this with a lot of my friends who have immigrant parents, and we all discuss the kind of weird neuroses of our parents that we all thought was a personal trait, but actually as an immigrant trait.

Okay, so they, you know, my mom, I love her dearly, but she has these sort of neuroses. You know, other friends were like, yeah, my, you know, my parents do that too. They're very scared to go out, you know, they, they like what they know. And then, you know, there's like some hoarding behaviors or catastrophizing.

And, and then I look at her and I compare her to all her brothers and sisters who never left their home. And she's completely different. They're all carefree and relaxed and very progressive and liberal. And she's sort of like. Yeah, she was like the odd one out and it throws into light this question of like, well, is it really aspirational to move abroad?

[00:29:57] Lucy: so That's so interesting. Yeah, because I was gonna, that is definitely, there's definitely an understanding, isn't there, that sort of, within a lot of cultures.

I think that to, even within like White Western cultures, this idea that like travel is progressive and like to settle elsewhere is like, you know, exciting and like you say aspirational, but. If the trauma is so run so deep, is it worth it?

That reminded me of the chapter in the book where you talk about is it yeet hay?

[00:30:22] Jenny: hey. Yeah, yeah.

[00:30:24] Lucy: And you basically contextualized the idea of yeet hay as it was passed on to you, and then you think about what it actually meant and it what could have been like undiagnosed depression or structural racism, or is that, is that kind of like where you were coming from in that?

[00:30:41] Jenny: Yes. Actually, that's a very good chapter to pick up, and that's probably one of the hardest chapters for non-Chinese people to understand because I don't explain anything. Yeah. Yeah.

[00:30:52] Lucy: it's, yeah.

Yeah. It's not a concept that I was familiar with. Yeah. But

[00:30:54] Jenny: It's a sort of, it's a, it's a cultural term that we all kind of intuitively know and that our parents kind of manipulate to get us to do what they want. It's, it's sort of like a popular belief.

[00:31:09] Lucy: Yeah. Wet hair gives yeet

hay was one yeah, yeah. You know what? As long as it's something they don't just, they don't approve of, yeet hay and, you know, how do you. Well, are we allowed to flip that back on our parents and point out all the things that, you know, all the behaviors that we also are concerned about?

Are you?

[00:31:28] Jenny: Yeah. Yeah. Are you? Yeah, I think so. And again, you know, we, it's very rare that we talk about mental health in our elders generation, but it's endemic and it, yeah, it's just that we didn't have the language, we didn't have the tolerance for talking about it Culturally, it's very um, taboo mm-hmm in within that generation.

Mm-hmm. It's very taboo to, to even, you know, get divorced, for example.

[00:31:52] Lucy: sure, yeah.

[00:31:53] Jenny: Yeah. To talk about depression, you know, what is depression? No, no, no. There's only two genders. Yeah.

[00:31:57] Lucy: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. You're fighting, there's a whole load of battles you need to fight

[00:32:01] Jenny: Yeah. About depression. Yeah,

[00:32:04] Lucy: yeah, yeah. That is, that is powerful then to be able to have those, I guess, like experiences and interactions with the people in the kitchen and feel like, okay, yeah,

[00:32:13] Jenny: here we

[00:32:13] Lucy: are.

I understand.

[00:32:14] Jenny: Mm, that's right. And

[00:32:16] Lucy: maybe you're doing the same for them.

[00:32:18] Jenny: I really hope so. I really hope so.

[00:32:21] Lucy: I wanted to talk a bit more about

Particularly I, one of the sort of branches of what you do that I really love are your knife videos the ones you've been doing recently and there was the snake and the chrysanthemum

in the chapter, in the book where you talk about knives, you talk about kind of this macho food culture associated with meat as well, and knives. Was kind of like using a knife and like making this content and writing about the book. Do you see it as a kind of reclamation, like, do you want to reclaim this skill so it's not just in that sphere?

[00:32:59] Jenny: Absolutely. I think you've hit the nail on that. Or carved the vegetable. Yeah.

[00:33:05] Lucy: Yeah. Softer, more feminine

[00:33:07] Jenny: Yeah. And bear in mind, you know, I wrote that chapter on the knife. A few years ago.

[00:33:12] Lucy: Ah, that's interesting. Okay. Yeah.

[00:33:14] Jenny: since then I've been working in a kind of traditional Chinese kitchen and sort of sharpening my knife skills and really enjoying

[00:33:22] Lucy: intended,

[00:33:23] Jenny: pun intended, pun Very much intended. Really enjoying it and realizing that it's such a beautiful craft. Yeah. And it actually isn't. A lot of people assume that, you know, using a Chinese cleaver is about strength and about this and that, but it's purely about skill. You know, you don't, you don't need to be particularly strong.

All you need to do is work hard and, you know, skill.

[00:33:46] Lucy: skill.

Yeah.

[00:33:47] Jenny: Skill and, yeah. And also breathe and focus

[00:33:49] Lucy: and,

[00:33:50] Jenny: mm-hmm. I think there are these beautiful, delicate things that you can create with knives, right? Yeah. And we often overlook those things in favor of like the big hunks of meat that you can carve and chop and yeah.

Yeah, I just really wanted to show the, oh, I hate to say this, but the femininity of a knife.

[00:34:10] Lucy: Hmm. Yeah. It's hard to kind of, like, you have to embrace the

[00:34:14] Jenny: Yeah,

[00:34:15] Lucy: To sort of like get away from one end of it. You have to, yeah. Sit more in the other, and, you know, even the, the title of that chapter, J is for Julienne.

Is there potential to dismantle the sort of language of knives. 'cause even, you know, this idea of Julienne, it's a French term and it is very, you know, it, it has a very specific meaning, but also it's just cutting a bat on of something like it. We don't have to call it a Julienne.

[00:34:38] Jenny: Mm, you're right. And what's beautiful about Chinese cooking language is it's absolutely beautiful. Like all the different culinary terms are worth learning in Chinese itself. And that's something I've been learning in the kitchen.

And we have all these different things that you can do with one cleaver. You don't need a whole set of knives, you know, you don't need a fish ting knife, you don't need a thing. Everything can be done with this one cleaver. And some of them have, you know, very kind of poetic names. So Julianne would be silk cut,

[00:35:14] Lucy: example. Hmm.

[00:35:16] Jenny: Which is such a beautiful analogy. Yeah. And you know that tofu dish itself that I described in the chapter called Kant tofu, also a thousand cut tofu.

Of course, it's not literally cut in a thousand pieces, but it looks like it's been cut into a thousand pieces. Yeah. And it blooms like a Kant. Chinese is very poetic, and the dish names are very poetic too. Mm-hmm. You know, as you know, I think that the more particular you are with language and the more fussy you are, the more beautiful and the more accurate or authentic it is.

So I encourage people to learn, you know, the kind of root term for something in the culture from which it originates.

[00:35:55] Lucy: Yeah, yeah, yeah. 'cause why would you kind of enforce another language and another entire cooking system on a cuisine that has its own name. It seems bizarre. Right?

It doesn't directly connect to this chapter, but actually what I love about, I think the thing that I love most about your writing in general, not just in the book, but you know, the work you do on social media and, on your website, it's just how funny you are.

Like your, your writing is so funny or like your, and I, you know, include video in that. Like the writing of all kinds is so funny and it really highlights like the potential for fun within these quite serious sort of conversations and circles, how, you know, kind of like overlapping and interacting.

You know, in the, in the book we've got a faux goop newsletter called gl. I enjoyed that a lot. Transcript of a keynote training speech by a lazy Susan, a fictional MA thesis about QQ as feminine and the diary of a rice cooker to name but a few. What was it about these forms of writing that felt right for what you were talking about?

[00:37:03] Jenny: Yeah, I'm glad you enjoyed those chapters.

I think humor is a very important sort of counter to some of the heavy topics in the book. Mm-hmm. Because, you know, the, the book pretty much ticks off, you know, like a lot of colonialism, cultural appropriation, fetishization, Oriental, you know, Oriental, and so. I just thought it was very wide with 26 chapters to play with.

You want a bit of levity in there? If only, for my sake,

[00:37:32] Lucy: Sure.

[00:37:33] Jenny: I was writing these chapters one, you know, on a monthly basis. Yeah. And. After, you know, a heavy month of research into Orientalism, maybe I just want to write a satirical piece. I think it's important to also distinguish between satire and parody and there's examples of both in the book. Satire...

I would would define as something that punches up with humor, with with periodic humor and parody being, let's say, something that is like grotesque exaggeration. So there is a parody, for example, of a WhatsApp conversation between a father and his son, but it is not satire because I'm not laughing at that dynamic. Yeah. But it is an, it is an exaggeration that almost every Chinese person I know will recognize and laugh with. Yeah.

[00:38:28] Lucy: Yeah.

[00:38:28] Jenny: Whereas the Goop parody is satire. Yeah.

[00:38:32] Lucy: Yeah. Okay. I get you.

[00:38:33] Jenny: I'm making fun at and laughing at the people who abuse that power dynamic where they will culturally appropriate Chinese, you know, practices without sort of paying the correct homage or even getting it right.

Mm-hmm. So, yeah. Yeah,

[00:38:49] Lucy: Yeah, that's, I really appreciate you kind of making that distinction. 'cause I think I haven't quite separated in my own head and that makes a lot of sense. And both of those forms that you describe are so different from other kind of parodies that we've perhaps seen of chinese people in white Western culture, you know, it's very important that you are doing it from your perspective and Yeah, but I, I think there is just, I think there is an expectation.

I, and I did notice that you'd shared an Instagram post where I. You shared a bit of a review where someone talked about these kind of sections, and I just thought that was it really? Like I just thought it was really interesting and I think it does, like, obviously it's personal taste, like everyone's entitled to their own opinion, but I, I'm not surprised by that response.

I guess from like a in within like mainstream food culture or media in general. I think people just sometimes think it's not okay to try and be funny.

[00:39:45] Jenny: Yeah. And they all p It is funny because the two reviews where I felt, I know you shouldn't read your reviews, but I've been reading the early reviews. Okay. Yeah, I, I really enjoy them. The two reviews where I thought the book was. At times misread or miss the mark were by non-Chinese reviewers. And again, I

[00:40:08] Lucy: bold move as well for publications to have

[00:40:11] Jenny: bold move.

I felt like they missed the point of the book where I said, well, some of this is not for you and you need to be okay with that. But also I think to, again, to decide what is funny and what isn't is an interesting one.

[00:40:25] Lucy: right?

[00:40:26] Jenny: Yeah. But I, I'm very open to critique because it means I can critique the critiques, you know?

It's a fair, it's, it's fair play. It's fair game. Absolutely. It's

[00:40:35] Lucy: It's cultural exchange.

Yes.

[00:40:37] Jenny: Non-transactional.

[00:40:38] Lucy: It definitely non transactional.

You are, you know, in part a Londoner, that is a big part of your identity.

How has London affected how you cook? It's a broad question, but are there particular restaurants that have been a really important place for you or particular places where you buy food?

[00:41:02] Jenny: Yes, I love London so much and I feel so privileged to live in London every day.

The way I cook is I base all my meals around plants and vegetables because I am primarily plant-based. And so. I've lived in several places in the last 15 years firstly in white chapel for a good decade, then in Haggerston and now I'm a new cross in South London. And the first thing I do when I move to places, scope out the local markets what we would call ethnic grocers uh, I think I even mentioned in the book, I dunno what the PC term would be like, urban bodegas. I think they were the urban Bodegas. Bodegas, yeah. British

[00:41:43] Lucy: Yeah. I like really like

[00:41:44] Jenny: Uh, And I'll see what they're selling, you know, so white Chapel obviously has a large sort of Bangladeshi population and the vegetable market there is amazing.

You can get all these South Asian

vegetables.

[00:41:55] Lucy: Mm-hmm.

[00:41:56] Jenny: you know, I love looking at what's in the one pound bowl section. In fact, today I got two types of ine

[00:42:02] Lucy: ine,

[00:42:03] Jenny: the. The fat ones, are they the Turkish ones and then they got the skinny ones? Which is what South Asians would use. Okay. Long and thin.

And in Haggerston, I was next to Hoxton Market, which has some really great Turkish owned. Sometimes they say Turkish, but they're actually Kurdish.

[00:42:19] Jenny: So Turkish slash Kurdish owned Green Grocers where I could get the best chilies and dried, you know, they had like these dried bergins again and um, pomegranates, you know, and then here in South London in New Cross, I'm close to Depford, which is a large Vietnamese population, and there's also a significant Latin American community here and Caribbean. So it's a real mix.

So I love to go on my weekly shop to the market and just see what I can get and base my meals around those. But I always use Chinese recipes 'cause I'm, I'm constantly, the only thing I want to cook is Chinese food or, you know, now, and again, south Eastern and Southeast Asian.

Yeah, mainly Southeast Asian. In a cold country you need, you know, something bright and spicy, I think.

[00:43:08] Lucy: Mm,

[00:43:08] Jenny: Mm, yes. And I'll use. Chinese recipes or cuisines as my lens onto those vegetables. Or maybe it's the other way around, you know? Yeah.

[00:43:18] Lucy: yeah.

[00:43:19] Jenny: So I'll look at the INE and think, well, we would do it this way, but this ine is slightly different.

So how will I, you know, how can I mesh the two

[00:43:26] Lucy: is the aubergine telling me that? Yeah.

[00:43:29] Jenny: And fascinatingly, I. As you know, I'm very passionate about language, so I'll look up the name of that vegetable in its native language and work out things about that vegetable. 'cause if you Googled, I think if you Googled it in English, you wouldn't really get the answer you

[00:43:47] Lucy: Yes, yes.

[00:43:49] Jenny: go back to the root name and sometimes I've found that, oh, it's just this Chinese vegetable. But a slightly different variety. I found that trick with green papayas, by the way, because green papayas are very sought after. If you are looking to make som tam, which is a, you know, very trendy Thai salad, it can cost 14 nine per kilo in an Asian supermarket, right?

But if you go to the South Asian markets, it's selling for five pounds a kilo. It just is listed as a different name

[00:44:22] Lucy: Genius.

[00:44:23] Jenny: genius. So

[00:44:24] Lucy: but that's also fascinating.

[00:44:25] Jenny: also fascinating. It is. Yeah. And once people cotton onto that, they're like, oh my God, why didn't I know that? I just need to go to white chapel and look for that thing.

[00:44:33] Lucy: Somebody's gonna be doing a shopping hack TikTok

[00:44:36] Jenny: Yes.

[00:44:37] Lucy: Yes. Before you know it. And, and what about your kind of more like your pantry? What are your pantry essentials and where do you get them?

[00:44:46] Jenny: My, my pantry is full to the brim with all kinds of Chinese dried ingredients. 'cause the brilliant thing about.

May, I would say, 'cause I'm most familiar with Cantonese cooking, is we use a combination of dried, preserved, sometimes fermented ingredients with very fresh ingredients because the Canton region has access to a lot of fresh produce. So fresh seafood, fresh vegetables which means that they don't, in our cooking, we don't really use much seasoning because

[00:45:19] Lucy: interesting. It's

[00:45:20] Jenny: very much about the, the clean flavor of the ingredient shining through. And the way you add flavoring with or depth to that light, fresh ingredient is sometimes with these preserved ingredients.

So fermented black beans is one that adds umami soy sauce, obviously. You sometimes use like fermented mustard greens and particular dishes. A lot of fermented fish products, so

[00:45:45] Lucy: oyster sauce

[00:45:46] Jenny: dried shrimp. So you have these many layers. In addition, once you. Once you understand the principles of how to cook, not necessarily what to cook, then I think that in itself can create a Cantonese meal out of anything, right?

Mm. I I always think it's not about the ingredients you're cooking with, it's the philosophy of how you cook and understanding almost like building a perfume or understanding how to talk about wine. It's like the top notes, the mid notes, the base.

[00:46:16] Lucy: Yeah. Yeah. That's not an idea or an approach that I hear communicated very much, if at all.

[00:46:23] Jenny: Mm.

[00:46:23] Lucy: And I don't, well, I feel like I, I, I mean, I don't wanna get into the

[00:46:26] Jenny: the authenticity. Yeah.

[00:46:27] Lucy: But I feel like there can be a lot of policing of dishes via ingredients, you know, sort of an implication that you have to have a certain thing to make it like this. And I think in lots of cases that that can be true.

But I really like the idea that, that's where creativity is sort of born by taking something that isn't maybe what they would cook with in China, but by applying the principles of how to cook with things in a Chinese way, whatever that might be, whatever region of China that might be, you can create a Chinese dish.

[00:46:57] Jenny: That's right. And you know, even when I've been doing plant-based cooking for a long time, you know, people say, well, you can never cook Chinese food if you don't eat meat. And it's, which is untrue because firstly there are doing doing it.

I've been doing it and there's all these subsets of, you know, veganism that no one knows about.

Well they do now, but, um. there are also dishes that are just, I hate this term, accidentally vegan. What do you mean is it's a vegetable dish, right?

[00:47:24] Lucy: Yeah.

[00:47:24] Jenny: Yeah. And the way that meat is used in pretty much most of China's regional cuisines is that meat is added last as flavor. Not necessarily as the main event, right? Mm.

So the meat, you know, a little bit of minced pork with the, with the dry fried green beans, adds umami and adds texture. So if it's umami and texture we're looking for, then we can just totally find something else that has umami and texture. You know, it can be dried mushrooms, it could be fermented black beans, right?

Yeah. It could be a little bit of crushed up toasted nuts.

[00:47:59] Lucy: Yeah. That also forces you. 'cause I think also we don't like, I think within sort of like often like Western food, we don't necessarily think of meat as like an ingredient. It's just like a thing that you cook with because that's how it's done.

But if you actually force yourself to reflect on what the meat is doing and what the meat is bringing to the dish, even if you leave the meat in it, it's going to, I feel like you're going to have a different relationship with that because there's going to be an appreciation of what it's doing within the context of the other ingredients, but then you can just replace it like you say.

So that's really nice. I really like that. Yeah. Yeah.

[00:48:34] Jenny: Yeah.

[00:48:35] Lucy: Finally before we finish celestial Peach is the platform you created quite a few years ago now, and the essays, as you've, you know, as you've said the essays in the book were self-published first which I think is really interesting and I guess like, I'm curious how you feel going from self-publishing to more traditional publishing, like how has that process felt and what do you hope to achieve from it?

[00:49:04] Jenny: think

I was very resistant to publishing a book. Who were you? I was at the very start and that's why I was self-publishing. Yeah. I, I

[00:49:16] Lucy: I, I

[00:49:16] Jenny: kind of, yeah, I contradicted myself about two thirds of the way in when I started at the A to ZI honestly didn't think I'd get further than C or D and it was kind of a, a project that came out of post lockdown and wanting to, wanting to sharpen my writing skills and researching skills and just find, find an outlet for long form writing. Where I could just say what I want. Really like, you know, internet rants, but with structure. Ideal. Ideal. And now everyone's doing it on substack.

[00:49:49] Lucy: You're ahead of the game. Yes.

[00:49:51] Jenny: But when I got to SI thought, you know what, I'm, I'm getting this live feedback loop every month because every essay I'm publishing, people are responding to it. You know, it is very thought provoking. I'm getting great sort of insight, you know, some people agreeing, some people not. But the main thing was that I knew I had a readership and I started seriously looking for an agent.

And then with my agent, we pitched to publishing houses. I wouldn't say the process itself has been frustrating, but it's slow.

[00:50:23] Lucy: Mm.

[00:50:24] Jenny: Mm. And that was kind of why I was very resistant to this idea of publishing a book. I knew it would be slow, slower than I usually move, which is at, you know, break Nets media.

Yeah. Yeah. And responsiveness. Right? And a lot of the essays were written in response to things. So if you read the book chronologically, you will see that it goes from almost this naive place of searching for authenticity through identity, you know, next topic, bat soup, you know? So that's very Corona,

[00:50:52] Lucy: very telling. Yeah.

[00:50:53] Jenny: Corona adjacent. And then all the way to the end, which lands on this almost acceptance of a communal kind of identity and sense of peace. But I think if I could do it again, I, I would go back and do ...nonfiction writing is very labor intensive, and I would definitely do all the right things such as proper footnoting and citation and getting people to sign waivers when I interviewed them.

Oh boy.

[00:51:21] Lucy: Oh boy, yes.

[00:51:22] Jenny: But it was the process itself that I enjoyed the most. As with anything, it's the doing. It's, it's the having the conversation. Yeah. It's doing that research. I don't care if, you know, in two years time, maybe one of the chapters feels a bit dated because it's a snapshot.

[00:51:39] Lucy: of a zap.